This is fifth in a series of posts on the Art Renewal Center. Today, I'm reprinting words by Brian Shapiro from the comments section here. I think it is understood that myself and Highlowbetween as well as members of our immediate blog family are painters and artists and therefore these thoughts from Brian, a philosophy student, are most welcome.

This is fifth in a series of posts on the Art Renewal Center. Today, I'm reprinting words by Brian Shapiro from the comments section here. I think it is understood that myself and Highlowbetween as well as members of our immediate blog family are painters and artists and therefore these thoughts from Brian, a philosophy student, are most welcome.

I regularly talk with Fred Ross and others who are involved in the Art Renewal Center, through the GoodArt discussion group list, and, because I often am studying art history on my own, send them collections of images to upload. I've always felt that the rhetoric of the organization was too militant, sometimes too simple, and sometimes shrill, and on the discussion group have often argued in defense of modernism. In fact there are many people on that discussion group who do that much more strongly than I do, but, for reasons that are obvious, its not uploaded onto the site archive. I also don't like almost all of the realistic art being produced as 'classical realism' and supported by the Art Renewal Center.

But, even though the arguments can be too militant or too simple, I think the basic ideas that are being argued aren't so misled. I've read the past three posts on this blog about the Art Renewal Center, and there seems to be a need to cast the people behind it as like 'conservatives', in one instance compared to evangelicals, to David Horowitz. From my perspective, most people who continue to argue against academic art or any type of traditional art end up being just as shrill and just as militant. (--and, as a coincidence, most people who end up politically opposing evangelicals end up being shrill and militant) Saying that there has been a 'conspiracy' to supress traditional painting is puffed up; but it is true that over time academic artists had been intentionally removed from history books and removed from museums, excused by the revolutionary agenda of modernism, and that traditional art has in academic papers often linked to everything bad---in short, the imperialist, racist, patriarchal [phallologocentric] Western society. There is a great amount of writing to this end. Sometimes couched in intellectual dialogue, sometimes emotional and shrill, but always reductive and militant.

If it has been political, and there is real value behind academic art; then its fair to argue about a political agenda in academia and museums that has supressed it. If there have been political reasons why our civic dialogue is biased a certain way, its also fair to target the media as being biased. This doesn't equate to paranoia... any more than tying Victorian beliefs to the bourgeois class structure is paranoia. I think there is a lot of erudition and intelligence among people in academics, but there is also politics--not necessarily what you'd say is left-right politics, though often it is, but in every field there is a favored ideology about the subject and its harder to get ahead if you have more than superficial dissent. That is to say--it is no different from academia in the 19th century, where the term 'academic' became perjorative. The 'bourgeoisie' to the avant-garde was not necessarily just an economic class, but the class of intellectual middle-men, it was the people who led academia and the 19th century intellectual discourse. People talk as if this applied to the 19th century but not the 21st.

I agree that a lot of people involved in the Art Renewal Center don't completely understand the 19th century, but I've found most professors in academia, whether in literature, art history, or philosophy departments, don't either. The 20th century was, by intellectuals and political movements, framed as an attack on the Victorian era, which was seen to be full every type of ill, and has been painted almost in ludicrous terms. Victorian thought for a long time, was the enemy--the 19th century was the enemy ... even fascism and naziism were framed as an attack on the 19th century, viewing modernism as a continuation of 19th century thought (The 19th century was to them, the century of the left, of liberal democracy, and abandonment of tradition)--even though you'll see postmodern intellectuals today try to argue that fascism and naziism were a product of the 19th century and its continuation.

To intellectuals, Victorians were prudes, dishonest, bigots, exploitative, uncreative,... rarely were they described in good terms, or their beliefs, their philosophy, or art given a second thought. And, apparently, to many, Victorians were this way, because they believed in things like truth and beauty and morality. I believe that our intellectual culture has been so much framed as an attack on the Victorian that we are estranged to a point where most people don't understand it--including most academics, who still believe in caricatures that were created a hundred years ago. But including conservatives, who by oposing intellectually popular ideas make themselves aligned with Victorians, but don't quite understand the depth behind Victorian beliefs.

Its not a bad thing to be conservative, and even if you're unable to present your argument in an way thats approachable to intellectuals, it doesn't mean you're wrong. I even think the beliefs of evangelicals have some truth to them that need to be recognized or acknowledged by intellectuals who are aloof to them.

There are points made in these blog entries to the effect that we need to make art thats new and different or relevant, or that academic art was the culmination of what started in the Renaissance. These are political 'talking points' of modernism. One of the points of the Art Renewal Center is to say that the goal of art isn't to try to be new and different and being so attatched to this idea can just as well lead to art that isn't new or interesting and the supression of anything that doesn't appear new even if it might be. I'm sure you realize that this is a flawed way of viewing art, and as its said "everything is contemporary." I understand modern art theorists and understand that they too knew the problem with this and would have believed that is a simplistic reading of what they were saying. But along with every intellectual argument, there is a politics that can't be escaped. You have had to repeat the same politics, responding to a call for returning to tradition with a demand that there be newness and relevance.

Academic art is still seen as not offering anything new or interesting, even though it did. People treat Victorians as if they were Puritans, which they weren't, as if their morality meant a complete repression of the body--which is brought up here, in faulting the restriction of a teacher encouraging life drawing to Victorian ideas.

Obviously, Victorians did not oppose life drawing---but its not an ironic exception to Victorian beilefs. Wherever you find an exception, I've found--its because something isn't fully understood. Victorians, framed in a certain way, seem less like prudes than modern people. Even sexless nudity is censored from television (while non-nude sexual situations are everywhere); while it was not nudity, not even depictions of sex, that was attacked by Victorians--but debased or valueless sexuality, inappropriate sexuality, prostitution, orgies, etc. When nudes were depicted in Victorian art they were shown sensually. Modern critics are divided by whether this means they were prurient, or whether it makes them cold and sexless--which just shows a lack of understanding. Victorians thought of sex differently than people today, and modeling them in terms of today's extreme conservatives will be a mistake. In the Victorian era, many governments, including France's, licensed prostitutes and checked for diseases. Manet's Olympia was not disliked because it was modern and sexual, but because it was felt there was no artistic merit in crudely and flatly depicting a prostitute. (to the avant-garde depicting this was what was meant by modern and sexual). To make nude women talk with suited men in Dejeuner seemed ridiculous and an assault on the values of propriety the audience had. The real problem with Victorians was not a thick-headed conservativism or hatred of the sex or the body, but a cultural dependence on stifling social conventions.

You could argue that the Victorian beliefs about sex and race, even if they had complications, were too easily reduced to prudery and bigotry--which has been argued. But that is a political result, and no different in this way than a modernist belief in constant change and revolution according to the times. Modernism has often been labeled a form of decadence, but more than an attack---many early modernist thinkers looked at decadence as a positive thing, and if broken down syntactically decadence is de-cadence, a loss of cadence, being dissonant--one of the foundations of early modern aesthetic theory. Sometimes people are too caught up in seeing the word as a political attack.

Victorians are blamed for women and minorities as being second class, but they were the first to try to bring them equalities. A story you'll find anyone at ARC knows is that Bouguereau was the person that opened the French academy to women, and many in the avant-garde remained chauvinistic. This is not to put things in equally black and white terms, but show the complications in condemning Victorians. People really haven't understood them.

As a result, now we have Victorian Studies departments in universities. Recent studies have also shown many ways in which the art world in the 19th century had many complexities and wasn't divided into a war between the bad academics and the good avant-garde.

But a lot of 19th century art history is still not understood, just because it isn't well recorded as a history. I've spent a long time on my own researching art in the 19th century and have found almost no text from histories to help me; I've had to piece together bits of information from different sources. Not only was there an intellectual basis behind academic art, but one that was original and different from Neo-classicism, something almost all art history professors don't understand. Albert Boime was the first to recognize this in his research on Thomas Couture, but didn't really place it in a developed view of 19th century history. The 19th century was vital with experimentation and different art movements before the Impressionists or even Pre-Raphaelites arrived.

There is a very interesting, relevant, and complex history to be told about 19th century art. Instead, for years we've been taught in basic, that Neo-classicism-> Romanticism-> Realism-> Impressionism. Now at least there is more of an acknowledgement that Academic art existed. People don't realize that for a while Neo-classcism wasn't even taught in art history. Ingres and David were believed to be at the root of the rotten tree that bore Bouguereau--hence the term, Pompier.

The same reason that Bouguereau is the center of the Art Renewal Center, is the same reason that Bouguereau was the center of attack for modernists. It was no accident that he played the role of the chief villain, and the reason is no more apolitical than when the Victorian era is considered in black terms.

The truth is, despite all of the bad rhetoric you might find in the Art Renewal Center, most people who are involved became involved because they discovered Bouguereau. This includes Fred Ross, who had been been an admirer or Renoir, and visiting a gallery with a Renoir he was taken aback and stricken by a painting by Bouguereau, only then to find, at that time, Bouguereau was worth pennies on the market--becoming a collector--and now its hard to buy a Bouguereau without millions. The belief that Bouguereau was a genius as an artist is a sincere belief, and not a 'strategy'. You'll find some people on the GoodArt discussion group who half-heartedly believed in modern art and professed a like for it until they saw artists like Bouguereau. I guess this does sound like evangelicals, in being born-again. But the power of art should be recognized as the power of art.

There is much to be appreciated in Bouguereau's paintings, and even though I don't fully agree with and support the ARC as a movement, as you don't, I think its necessary for a re-appreciation. Whether or not you want to place Bouguereau in some pantheon or canon is besides the point to realizing he was an important and great artist. But I'm not opposed to having him in the canon---I realize his art as being more than just cherubs or pretty girls. Rembrandt's art wasn't perfect either, I can find a lot of mediocre Rembrandts--and as an artist he was obscured for 200 years after his death until he was rediscovered in the 19th century. Something Fred Ross is fond of saying is that while Rembrandt is the master of depicting old age, Bouguereau is the master of depicting youth.

Innocence is one of Bouguereau's themes, and its often in simple terms mistaken for over-sentimentality. Innocence was a popular subject among academic artists. Innocence was one of Tchaikovsky's themes, he used fairy tales. For years after his death, Tchaikovsky's compositions were considered sentimental kitsch, he was considered the arch-conservative of the music world, like Bouguereau was considered the arch-conservative of the painting world. If music theory had the same discourse as art theory, Tchaikovsky would be called academic and not romantic. In Austria, the academic painter Hans Makart was friends with Richard Wagner, and both explored their mediums in similar ways. Doubly unfortunate for Makart, aside from being an academic, he was Hitler's favorite artist.

The importance of Rembrandt is also not just that he chose to depict a subject that you find meaningful--surviving suffering--but that he ws able to express it by developing new ideas and techniques in art that separated him from the Renaissance, including his increased naturalism and use of impasto. Something similar can be said about Bouguereau.

In every field representatives of Victorian culture were first demonized, then obscured. In philosophy, this was Victor Cousin, who is just recently being re-examined. Victor Cousin had inspiration from an 18th century philosopher, Thomas Reid. Most people haven't heard of him either; but he was well known for over a century, and was David Hume's rival. Of course, David Hume is liked because he deprecated metaphysics, and Descartes, two things that became popular to deprecate post-19th century.

Modern intellectuals, of course, the wisdom goes, are not bourgeoise and will not be overturned and forgotten by a new movement, they are just built on.

I'm not someone who wants to attack and bury 20th century intellectuals, I don't think they were all dumb. But I also don't think 19th century intellectuals were all dumb--and acknowledging that requires questioning the basis of 20th century philosophy, questioning the attack framed on Victorian culture, Western culture; not playing around it. It means to put 19th century ideas and 20th century ideas on par. And liberalism and conservativism, in general terms, on par. The idea of absolute objective truth and relative subjective truth, on par.

If there's a "angry white male" mentality that everyone else is stupid, there's a mentality that angry white males are stupid. While people attack the bigotry of Western culture in placing itself above others---too often is Western culture attacked and named as the source of all of our problems. For some reason you shouldn't judge cultures in places that are foreign to us, but its okay to judge and condemn the culture of a period in history 100 years ago.

I would guess the reason there is the need to talk about the people in the Art Renewal Center being like conservatives--and politically, they all aren't--is that you don't see how much political agendas are involved in academia. I don't consider myself among conservatives either, but I don't consider myself among liberals.

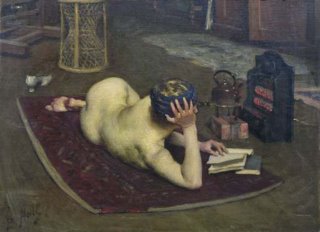

Image: Lindsay Hall (1859-1935), Nude Reading at Studio Fire, Oil on canvas, 1928, 19 3/4 x 27 inches (50.29 x 68.58 cm), from the ARC museum.

I am probably sitting on about a half-dozen posts that remain un-solidified. Oh well. Have been reading these Donald Kuspit chapters, trying to keep up with them anyway. Here is a little sample of what I thought was fun.

I am probably sitting on about a half-dozen posts that remain un-solidified. Oh well. Have been reading these Donald Kuspit chapters, trying to keep up with them anyway. Here is a little sample of what I thought was fun.

The real problem with blogging now is doing it in an atmosphere of state sanctioned and industry sacralized Dada. Dada hopelessness all the time. Outside of the Ivy-Leagues it is Dada nihilism as far as the eye can see.

The real problem with blogging now is doing it in an atmosphere of state sanctioned and industry sacralized Dada. Dada hopelessness all the time. Outside of the Ivy-Leagues it is Dada nihilism as far as the eye can see.